Artist Story: EC Davies

EC Davies photographing participants at The Late Shows, Vane, 2014.

Please give an introduction to yourself as an artist.

I don’t think there was one singular thing that made me want to be an artist. I grew up in between Manchester and Liverpool, spending a lot of time during my early years at my grandparents. Together we would watch old films on TV. They would know all the names of the actors of the silver screen and words to the songs in musicals. My favourites were the silent movies by comedians like Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. Salvador Dali described Buster Keaton’s work as ‘Anti-Art’, and said his use of inanimate, mass produced objects was pure poetry. To me, his work directly reflected the illusory nature of the moving image. You could see the trickery directly in the action sequences, as well as his physical agility and skill at manipulation. Coupled with Keaton’s deadpan ‘look’, I was mesmerised. It was how this world was made, the special effects and animation that interested me.

I had dreams of working in the film industry at around the age of 15, but no idea how to go about it. It wasn’t until I left home and moved to Manchester a few years later that being an artist became a possibility and was reflected in the people I met who were involved the music and dance scene. There was a Do it Yourself attitude in Manchester and Liverpool especially evident in organised raves and pirate radio stations. The stations had female DJs and also played a lot of music by women. I saw lots of live music including bands, New Order, 808 State, Public Enemy and many more.

I did various jobs at the time including giving out flyers outside the Hacienda for their R&B night, waitressing and also working in sweatshops (sewing buttons on aprons). I think it was a mixture of the self-learning traditions of both my English and Welsh grandparents, the backdrop of industry – as both sides of my family had worked in mines and textiles factories – and the rich cultural electronic music/dance scene I was part of that encouraged me to go to art college.

As an undergraduate I found a bag of fashion promo booklets for some fashion label in a plastic bag in an alley in Manchester. I spent at least one year collecting flyers for events in and around the North West and cutting and pasting what I found into the booklets. These became a series of visual diaries: a mix of collage, drawings and text. I was influenced by the cut-ups and an automatic way of production, first championed by Dada and later writer William S Burroughs, and artist/poet Brion Gysin’s long-term collaboration, the Dreamachine, a stroboscopic light device that used visual stimuli to draw out images from memory.

I liked the way you could create something extraordinary from discarded ‘ordinary’ objects. The books said a lot about the times I was living in without following a traditional narrative structure. Pattern, repetition, rhythm, movement, games and the use of everyday inanimate objects have always been themes in my work. I had this obsession for lens-based media, but it wasn’t until later when I was doing my Master’s course that I was able to consolidate my interests by making my first video works.

Wrap Your Head in Tape, 2011, video

Spring, 2016, video

You often appear as different characters in your work but mask/hide the faces in the works. Could you expand on this?

Oscar Wilde said that “Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth.” Masks provide anonymity, a sense of ritual and a sense of freedom. From 2012 onwards, I worked with the body, gesture and movement. I used masks initially for formal and compositional reasons. I wanted to remove any facial expressions that would distract from the way the body expressed itself and moved.

I usually work alone, so I do everything, from filming to editing and postproduction. It provides me with boundaries. These pieces are influenced by Andy Warhol’s ‘slow cinema’ portraits. Warhol’s Factory ‘sitters’ were still, unmasked and couldn’t see their reflection. They were a mixture of regular people and film stars. Warhol slows the footage down for playback, intensifying how the camera picks up even the smallest of movements and facial expressions. In my videos the opposite is at play. I am masked so those small movements of expression are invisible, I see myself as forms and shapes reflected in the camera’s viewfinder. It is a very visual and intuitive experience, following instructions that seem to have no purpose. When I film it’s a bit like a game: I have the outfits, props and music which are cues for the performance. My actions are automatic, chance is therefore a big part of the work, as I have no idea of the outcome. The performative experience of sorting, dancing or whatever is consuming in the moment. It’s kind of contradictory in nature when I know it will be shown in public, but maybe that’s what gives the absurd quality which I like.

The action in the video, Wrap Your Head in Tape (2012), exemplifies this. It’s a single-take piece that shows me wrapping my head in tape and then removing it with scissors. I slowed the footage in edit making each movement more vivid. The action is taken out of context, there is no explanation as to what’s going on, no traditional narrative structure. In reading that action, are we using our understanding of cinema and how we have been trained to understand its workings and is that why we feel uncomfortable when it doesn’t follow the normal plan?

The characters are often depicted performing one, or a set of, obsessive, repetitive and mundane tasks, usually with no apparent end ‘purpose’ or result. Why is this?

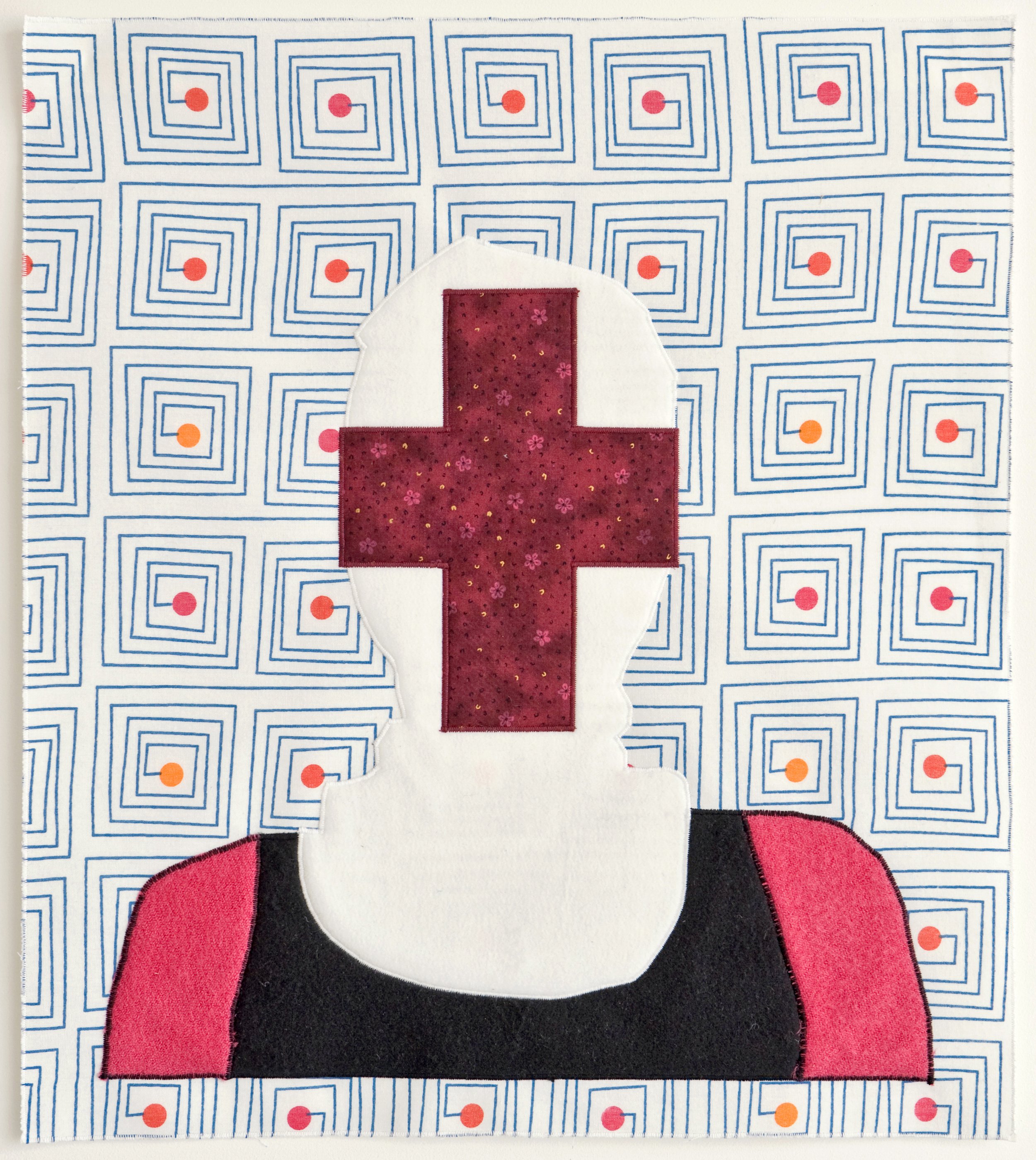

Repetition and pattern mimicked or reflected in music or the notation of music is kind of mathematical and rhythmic. Collecting and recording have a kind of organisation to them which is important for me. Sewing and using second-hand textile remnants used to have a negative element to it, as it meant you were poor, as evident in Dolly Parton’s song, Coat of Many Colors (1971). But in recent years it has been recognised that sewing in its repetition and preciseness can have a calming effect for the maker. This was evident when I saw an exhibition of quilts made by inmates at Wandsworth Prison in London. The written statements of the male prisoners described the calming effects of sewing and how it had reduced fights and violence in general. It sounded like a meditative experience, one that I needed at the time, and an example of how art can help deal with trauma and healing.

You often use certain utilitarian objects, such as rubber gloves, balaclavas and duct tape. Can you expand on your reasons for this?

There are both beauty and ugliness in the ordinary, everyday object. I mean, where did it come from, how far did it travel and how many people did it meet on its journey to the vending machine or the kitchen table? How much pollution was caused in its production, were people responsible for creating that object paid enough, their living conditions, etc. Objects like gloves, masks, duct tape, etc. are loaded with inherent contradictions: on the one hand they have useful, practical, even protective roles but conversely, we witness these objects in narrative cinema, the news, or traumatic experiences, evoking violence, terrorism and war.

Can you expand on your interest in notions of ‘the feminine’ in your work?

Both my Grandmothers (English and Welsh) could sew, knit and crochet, this reflected a strong working class, self-education tradition in the Welsh valleys and North of England when heavy industry and the Trade Union movement had a strong presence. My mother wasn’t taught to sew and none of these skills were passed down to me. However, sewing in these villages and towns was a communal act, and my dad describes his upbringing in Merthyr Tydfil as a matriarchal system surrounded by very strong women. When I made the series of quilts or wall hangings made from old wooden blankets with fortune cookie text sewn onto them, I suppose I was thinking of Trade Union banners and marching but also these strong female figures.

In Ukrainian-born filmmaker Maya Deren’s film, Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), there is a scene where Deren is shown wearing a mirror as a mask. She believed that through dance one could be merged with the transcendental: something ‘other’ that was a move away from the cult of personality and the idea of the big star in the Hollywood studio system.

In my first solo show at Vane, ‘Flatland’ (2006), I employed the same approach. I used an atomic force microscope (AFM) that goes beyond lens-based microscopy to image surface contours on a nano-scale – a nanometre being a billionth of a metre. ‘Flatland’ was a two-screen video projection transcribing the mapping of the AFM into slowly emerging topographical contour lines, visualising the hidden surfaces of materials. I had been reading the book by theologian Edwin A Abbott, Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions (1884), a satire on Victorian culture, class and gender-roles. The story describes a two-dimensional world where the sexes are different geometric shapes: women are simple line-segments, while men are polygons. Men can ‘evolve’ over generations, resulting in a rise in social status, though strictly controlled, with irregular polygons being killed at birth. The same is not true for the women, who never evolve beyond being straight lines and suffer a form of apartheid, even having to use separate entrances to buildings.

The characters in your work appear as ‘other worldly’, with their own, often ritualistic, behaviour patterns. Does this have anything to do with the self-image expectations placed on us, and specifically women, and notion of what is ‘normal’ behaviour?

There is an ‘other worldly’ nature to film in general: an elevation of status of the framed scene. I try not to think of what is expected and what isn’t, as I feel those constraints are already there, subconsciously. I’ve always loved dance and singing: the feeling of cathartic freedom. The same is true with sewing: there’s always a period of research and discomfort – driven by fear and self-doubt – but once the making starts there’s a sense of liberation. The research can also be really rewarding but you have to know when to stop; when to start sticking with the decisions you have made without fear.

In the digital print series,Wallflower Prison Angels (2012-13), each character or persona is identified with a specific wildflower and its characteristics – mimicking scientific language of classification that emphasise labelling, leaving little room for interpretation, for a deeper understanding. I had a collection of second-hand dresses that I had been attracted to because of the fabric designs and their silhouettes. The 28 characters were developed from photographs of myself masked and wearing different outfits. These simplified, anonymised images do come across as ‘other worldly’, but they gave me room to explore self-expression through subtler means: physical stance, colours and ideas of fashion. Labels can be confining but also liberating – the comfort of belonging, having a support group.

Could you say something about the participatory / performative work?

The participatory work started from small interventions, and grew into larger, more focused collaborations. I spent time with various creative community organisations and groups, including choirs, to learn how these groups worked and how I could involve people by making my work more accessible. When I presented the participatory piece, I’m Sticking With You, at the Sounds from the Other City event at Islington Mill in Salford (2017), it was in front of a music crowd and I wasn’t sure how it would go down. People were asked to wear a felt mask and throw dice to have the chance of winning ‘love heart’ dolls that I had made out of leftover fabric from the masks. I was amazed at how people took to the game. Grown men were doing somersaults as they threw the dice and were over the moon to receive their love heart dolls, insisting on having their picture taken wearing their love heart masks next to the scaffolding where the dolls were hanging!

For the video, Follow my Leader, shown at Vane in the solo show, ‘Press Play and Record’ (2017), people visiting the exhibition were filmed in the gallery. This footage was then added to the video being shown. This meant when they re-visited the gallery they could see themselves in the main video work as it continually grew and evolved.

Does your adoption of multiple characters or personalities represent a desire to resist the common desire for the viewer to read an artist’s work as autobiographical?

Film director Federico Fellini was famous for saying “all art is autobiographical; the pearl is the oyster’s autobiography”, but he also claimed that calling his own work autobiographical was “a hasty classification”. Working in film is generally a process that involves many individuals and in that sense is influenced by multiple perspectives. Maybe that’s why Fellini refers to ‘autobiographical’ as being a hasty classification for his work?

The painter Lucien Freud, however, said “everything is autobiographical and everything is a portrait, even if it’s a chair”. Working alone I respond to things that happen in my life, good and bad. I deal with themes of loss, trauma and ideas of togetherness. I play multiple characters, but my work also involves multiple participants. In order for it to be enjoyable, accessible and fun, the work doesn’t have a ‘confessional’, autobiographical element to it. It does however, deal with serious, personal/political ideas by default. I think that through the act of creating – making, singing or dancing as part of a group – being part of something bigger than oneself, one can heal or at least feel less alone. Being part of something creative in an active and not passive way can open us to different life experiences that have a positive influence on the way we feel about ourselves and others.

Do you have any particular memories of your experience of working with Vane?

Vane directors Paul and Chris have been my mentors and friends for twenty years. They have always encouraged and supported my practice; helped with the challenging technical requirements of the installation of my work and the development of the live participatory element of my work. They commissioned essays to accompany my gallery exhibitions that helped put my work in a critical context and secured interest and exhibitions in London, Berlin and elsewhere. When I moved to Berlin, Paul and Chris were very helpful, introducing me to Berlin-based fellow gallery artists Jorn Ebner and Kerstin Drechsel, as well as curators from Berlin galleries such as September and Scotty, where I went on to exhibit.

Even though I haven’t constantly been part of the Newcastle and Gateshead art scene over the years, because of my connection with Vane I have never been completely out of the loop. I think that Vane and the artistic community in Newcastle and Gateshead not only gave me access to many opportunities – exhibitions, commissions, mentors, technicians – more importantly, they gave me a sense of grounding, of belonging.

‘Press Play and Record’, solo exhibition, preview, Vane, 2017