WO/

9-24 March 2018

‘WO/’, 2018, installation view

‘WO/’, 2018, installation view

‘WO/’, 2018, installation view

‘WO/’, 2018, installation view

Clémence BTD Barret, Lucy Bird, Katie Bishop, Liz Blum, Samantha Boyes, Kerry Ann Cleaver, Maria Ferrie, Emma Fleming, Roberta Louise Green, Paddy Killer, Lady Kitt, Bex Massey, Jenny McNamara, Marisol Mendez, Pelumi Odubanjo, Jennifer O’Neill, Louisa Rogers, Lizzie Rowe, Tracy Satchwill, Georgina Talfana.

‘WO/’ is curated by artists Melanie Kyles and Caitlin Heaney to mark International Women’s Day on 8 March and showcases work on the themes of the feminine experience, identity and expectations. The exhibition raises questions regarding what it means to be a WO/man in the modern era, through the perspective of female-identifying artists and their work.

‘WO/’ explores the open-ended fluidity of womanhood; the disparate experiences of each female-identifying artist featured in this exhibition. ‘WO/’ artworks will explore areas of feminine identity: how do past expectations and influences affect women today? Which parts of feminine heritage do we bring forward, and which now feel outdated? How do these themes relate to society’s ever-changing gender constructions?

The theme for this year’s International Women’s Day is Press for Progress, which focuses on gender parity and acknowledges movements working towards global gender equality. ‘WO/’ aims to allow feminine-identifying artists to have a platform to share their stories of societal and gender expectations, sexual and gender identity, heritage, reclaiming the feminine voice, and economic inequality, with a diverse mix of twenty UK-based and international artists.

Clémence BTD Barret’s video, borderline.china (2017), tells a story of a dilemma: images of a Chinese woman’s face stare out at the viewer, while a voice-over whispers a monologue in Mandarin of her desires and struggle to be accepted as an independent, strong woman within a male dominated society.

Lucy Bird’s sound work, In (side) Out (side) (2018), consists of headphones placed on a red circular rug through which a female voice repeats the words ‘inside and outside’, abstracted into different formations. The work explores shifting female ownership of language in a domestic and sexual context: an act of questioning barriers, of protest, and of reclaiming the private/public female voice.

Katie Bishop’s digital photographic work, Madonna (2018), is a dark nightmare of the male gaze depicting a constructed female deity: Marigold gloves, blonde wig, head scarf, an Adidas jumper clash and collage together symbols of women, creating a character that provokes a sense of unease.

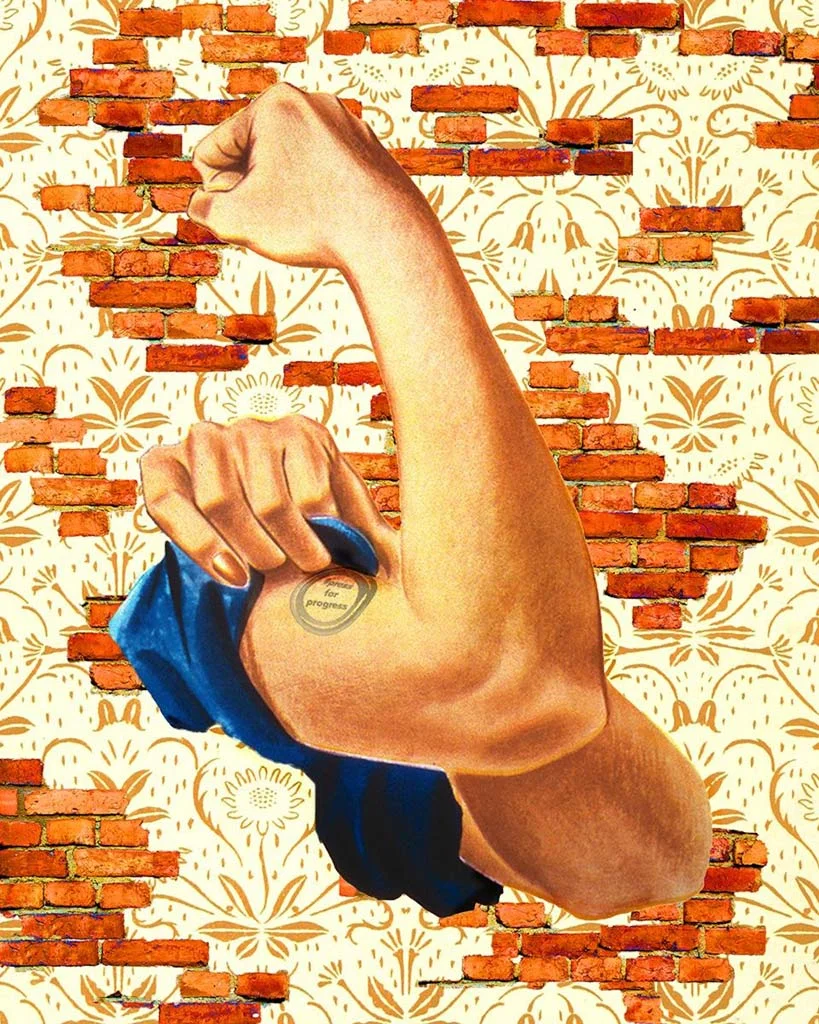

Liz Blum’s Break Barriers (2018) is one of a series of prints illustrating pay inequality, the struggle with patriarchy and ‘mansplaining’ – a portmanteau term for a man explaining something, typically to a woman, in a condescending, patronising manner – echoing government public announcements and protest posters.

Samantha Boyes’ Anna – The Model’s Maillol (2017), a female figure cast in bronze, is an homage to the French sculptor, Aristide Maillol. However, Boyes’ subtle subversion with missing toes and extended index finger creates a defiant gesture despite the figure’s bowed and otherwise submissive stance.

Kerry Ann Cleaver’s More Than Just a Pretty Face (2018) combines found materials, including slate and 1960s men’s magazines ranging from ‘glamour’ photography to motoring, to explore the interchangeable language of femininity in the modern age through the use of the female form abstracted and intertwined with other elements.

Maria Ferrie’s series of photographic prints, Inadequate (2015), show individuals within intimate spaces, unique to each sitter yet each holding a sense of familiarity. The viewer’s experience of the images in accordance with their own understanding of loss, loneliness and the relationship between memory and identity.

Emma Fleming’s photographic work, Queering Femininity: Push The Button (2018), allows the viewer to enter the artist’s queer vision of ‘feminine expression’. There is juxtaposition between the sexual connotations of pushing buttons and the taking a piece of masculine/feminine fruit from a bowl. Taken together, the images represent the ‘Madonna’ and the ‘whore’.

Roberta Louise Green’s series of ink drawings, Goat Man and the Mountain Witch (2017), create a sense of identity and place. The male character reflects the positive influence of Green’s current relationship. However, though the drawings are set in pairs, the separate sheets communicate a sense of isolation.

Paddy Killer’s painted constructions, Anatomy of Change (2018) and Walled In (2011), illustrate key ordeals in her life: the former, life-long disease, not diagnosed as organic rather than psychosomatic until later life, and the latter the trauma of her home’s destruction. They speak of women’s pain not being taken seriously, of being told to ‘grin and bear it’.

Lady Kitt’s 109 Ways You Are Worth More To Me Like This – Portrait of Khadija Saye (2018), is from the series of altered bank notes, ‘Worth UK’, inspired in part by feminist activist Caroline Criado-Perez’s campaign to have Jane Austin’s image on the UK £10 note and the abuse (including death threats) Criado-Perez received for wanting to celebrate the achievements of women in the same way those of men have been celebrated for years.

Bex Massey’s digital print work, The Swing (2016), taken from the series #MAMCONCURS, is based on the 18th century French artist Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s painting of the same name, and uses allegory and the throw away nature of British popular culture to question the way women are depicted in art history.

Lucy Bird, In (side) Out (side), 2018, looped audio, MP3, headphones, carpet, 1:10min

Lady Kitt, 109 Ways You Are Worth More To Me Like This – Portrait of Khadija Saye, 2018, Bank of England £50 note, glass vial, 33x33cm

Jennifer O’Neill, Feminist Fuel, 2018, mixed media, 14x20cm

Jenny McNamara, Stripey Buoy, 2017, ceramic, rubber, 66x100cm

Jenny McNamara’s sculpture, Stripey Buoy (2017), explores the fit between two materials: ceramic and plastic, the tension between them and their differences – the strong lines of the ceramic against the weightlessness of the pink plastic. She references fluidity, a visual representation of expression – her thoughts, her experimentation.

Marisol Mendez’s, photographic work, About ‘aDicktion’, a love story (2017), exposes the pathos of Mendez’s romantic (mis)adventures in London. Repossessed by their owner, tales of love and heartbreak become a vehicle for humour, resistance and self-expression, drawing inspiration from the likes of Nan Goldin, Tracey Emin, Chris Kraus, and Lars von Trier.

Pelumi Odubanjo’s Twenty-something (2018), is a series of photographs, intimate in both proximity and subject, of a friend playing with various obscured forms of food. This juxtaposition of the visceral food, lurid red and the material beauty more often represented in images of young girls, challenges the portrayal of feminine beauty and reality.

Jennifer O’Neill’s, Feminist Fuel (2018), comes from the ongoing work, Millenni-Med, ‘the medical company founded to save Millennials’. O’Neill introduces a new ‘Feminist Fuel’ especially for International Women’s Day. The piece aims to put into question everything that is right and wrong with the commercialisation of political movements.

Louisa Rogers’ fabric sculpture, The Sartorial Paradox (2018), consists of a tapestry-like length of cloth showing an image of a bejewelled model as timeless elegance. The juxtaposition between this image and the impersonal, technological printing process used to produce it, speaks of the uncomfortable paradoxes of a femininity that at once wishes to embrace and indulge in the sartorial but remain detached and critical of the world it espouses.

Lizzie Rowe’s painting, Sixty (2015), is a direct self-portrait celebrating sixty summers, deliberately monochromatic to emphasise the documentary nature of piece. With much of her previous work featuring traditionally feminine dresses, both worn by Rowe and depicted on their own, ‘Sixty’ is a raw and authentic snapshot in time.

Tracy Satchwill’s animation, Hysterical Females (2017), marks the 100th anniversary of the Representation of People Act 1918, which allowed (only some) women over the age of thirty to vote in the UK for the first time. Satchwill’s female protagonist faces discrimination at every turn in a surreal, patriarchal Edwardian world.

Georgina Talfana’s ink drawing, Me, my mum and the Madonna del Prato (2018), details the many faces of a mother: from Talfana being held by her mother as a baby in 1976 to the artist at week 20 of her pregnancy in 2017. The symbolism of a bird with a serpent in its bill as depicted in Italian Renaissance painter Giovanni Bellini’s Madonna del Prato, relates the struggle between good and evil, and for Talfana, the estrangement of her own sister and mother.

Take a video tour of the exhibition

Share this page